Re: GÉNERO

Publicado: 30 May 2019, 01:24

Sigo con el libro

These attitudes, assumptions and prejudices are hard-wired into us: not into our brains (there is no neurological reason for us to hear low-pitched voices as more authoritative than high-pitched ones), but into our culture, our language and millennia of our history. And when we are thinking about the under-representation of women in national politics, their relative muteness in the public sphere, we have to think beyond what some prominent British politicians and their chums got up to in the Oxford Bullingdon Club, beyond the bad behaviour and blokeish culture of Westminster, beyond even family-friendly hours and childcare provision (important as those are).

In the Afghan parliament, apparently, they disconnect the mics when they don’t want to hear the women speak

At this point, it may be useful to start thinking about the classical world. More often than we may realise, and in sometimes quite shocking ways, we are still using ancient Greek idioms to represent the idea of women in, and out of, power. There is at first sight an impressive array of powerful female characters in the repertoire of Greek myth and storytelling.

In real life, ancient women had no formal political rights, and precious little economic or social independence; in some cities, such as Athens, ‘respectable’, elite married women were rarely seen outside the home. But Athenian drama in particular, and the Greek imagination more generally, has offered our imaginations a series of unforgettable women: Medea, Clytemnestra and Antigone among many others. They are not, however, role models – far from it. For the most part, they are portrayed as abusers rather than users of power. They take it illegitimately, in a way that leads to chaos, to the fracture of the state, to death and destruction. They are monstrous hybrids, who are not, in the Greek sense, women at all. And the unflinching logic of their stories is that they must be disempowered and put back in their place.

In fact, it is the unquestionable mess that women make of power in Greek myth that justifies their exclusion from it in real life, and justifies the rule of men. (I can’t help thinking that Perkins Gilman was lightly parodying this logic when she made the women of Herland believe that they had messed up.) Go back to one of the very earliest Greek dramas to survive, the Agamemnon of Aeschylus, first performed in 458 BC, and you’ll find that its antiheroine, Clytemnestra, horribly encapsulates that ideology.

In the play, she becomes the effective ruler of her city while her husband is away fighting the Trojan War; and in the process she ceases to be a woman. Aeschylus repeatedly uses male terms and the language of masculinity to refer to her. In the very first lines, for example, her character is described as androboulon – a hard word to translate neatly but something like ‘with manly purpose’, or ‘thinking like a man’.

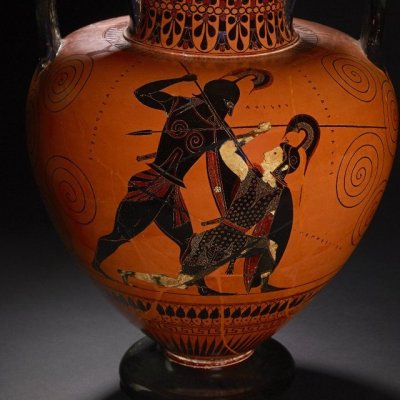

And, of course, the power that Clytemnestra illegitimately claims is put to destructive purpose when she murders Agamemnon in his bath on his return. The patriarchal order is only restored when Clytemnestra’s children conspire to kill her. There’s a similar logic in the stories of that mythical race of Amazon women, said by Greek writers to exist somewhere on the northern borders of their world. A more violent and more militaristic lot than the peaceful denizens of Herland, this monstrous regiment always threatened to overrun the civilised world of Greece and Greek men. An enormous amount of modern feminist energy has been wasted on trying to prove that these Amazons did once exist, with all the seductive possibilities of a historical society that really was ruled by and for women. Dream on. The hard truth is that the Amazons were a Greek male myth. The basic message was that the only good Amazon was a dead one, or – to go back to awful Terry – one that had been mastered, in the bedroom. The underlying point was that it was the duty of men to save civilisation from the rule of women.

Pentesilea se distinguió por sus numerosas hazañas ante la ciudad asediada antes de ser abatida por Aquiles, quien atravesó su pecho con una lanza. Al verla morir, Aquiles quedó sobrecogido por su belleza y cuando Tersites, uno de los soldados griegos, se burló de él por esta pasión, Aquiles le mató. Diomedes, primo de Tersites, arrojó en venganza el cuerpo de la amazona al río Escamandro. Según otras versiones, fue Aquiles quien la enterró en las orillas de ese río.