Hola. Hace años vi Jane Eyre (sí,por Fassbender) y me figure que su director era un señor ingles o algo así...Cuando vino True Detective la descarte por completo sin pensar, porque nada ni nadie me convencería de pasar 8 horas de mi vida viendo a McCoune haciendo lo que sea.

Me dio curiosidad ver Maniac por Emma Stone y la acabo de terminar, me he leído como tres entrevistas a Fukanaga para entender su visión de la historia y la verdad es difícil no amarlo, porque literalmente las entrevistas y las fotos son lo más perfil de Tinder/Eharmony que he visto en medios escritos jamas

...

By Willa Paskin

Sept. 11, 2018

At the end of 2009, the director Cary Joji Fukunaga was hunting for his second feature film. His first, “Sin Nombre,” had been an almost preposterously ambitious undertaking for a first-time filmmaker, tracking the intertwining stories of an immigrant and an erstwhile member of MS-13 as they made the dangerous journey to the United States border atop fast-moving train cars, all written by Fukunaga in slang-heavy Spanish. Over the course of two years, he made multiple trips to Mexico, riding the real-life version of these trains and visiting prisons in Chiapas to make connections with gang members who could help ensure that the film had a documentarylike accuracy. “I need to believe what I’m watching,” he says.

Second movies, Fukunaga had been told, mattered more than first ones. They showed what kind of director you really were: one who waited for the perfect thing, or one who was prolific, experimental and didn’t repeat himself. Fukunaga knew he wanted to be the second kind. So the film he chose to make after “Sin Nombre” was wildly different from its predecessor: a period costume drama. His adaptation of “Jane Eyre,” Charlotte Brontë’s classic novel, starred Mia Wasikowska and Michael Fassbender as a particularly smoldering Rochester. It is both exceptionally haunting and powerfully romantic — a horror story and a love story — and it required an entirely distinct directorial approach. “At first,” he recalls, “I was like: What do I do with the camera? It just sits there? But I really wanted to do a study on composition and restraint. Especially in my generation and younger, there’s this impulse to cut, to move and do things all the time, and I was trying to figure out how to do as little as possible.”

Fitting the entirety of “Jane Eyre” into a two-hour movie sometimes felt to Fukunaga like “a real sacrifice — the ability to explore characters for many hours was a sort of itching desire at that point.” And so he turned to television. In 2013, he directed the entire first season of HBO’s metaphysical crime series, “True Detective,” written by Nic Pizzolatto and starring Matthew McConaughey and Woody Harrelson. Television has historically been considered a writer’s medium, and film a director’s one, which is another way of saying that on TV, writers usually have the power, and on movies, directors do. The sheer quantity of footage that needs to be shot for a TV show, often on tight turnarounds and smaller budgets, means that series are typically passed like a hot potato from director to director while the cast, crew and showrunner — who is often the writer-creator — attend to larger questions of continuity, plot, tone and style. Even when a TV show is in the hands of a great director, that person typically only sets the show in motion (think Martin Scorsese directing the pilot of “Boardwalk Empire”) or puts her imprint on a few stellar episodes (think Michelle MacLaren and the episode of “Game of Thrones” with the bear fight).

But Fukunaga was not an unequal partner in “True Detective.” His sensibility can be felt in the gorgeously eerie, rock-steady tone that suffuses every frame of the series, so precise and overgrown you can almost smell it. His work made the most convincing case yet that a distinctive directorial viewpoint could, on TV as in the movies, be as qualitatively important as good writing — could perhaps even make up for overwrought writing. (The second season of “True Detective” was written by Pizzolatto, but not directed by Fukunaga, and without him, the series took a pretentious nose-dive.) With “True Detective,” Fukunaga was at the forefront of a new directorial approach to TV — one that includes David Lynch’s reboot of “Twin Peaks” and Jean-Marc Vallée’s work for HBO on “Big Little Lies” and “Sharp Objects” — in which directors are intimately involved with every aspect of a series’s many episodes, a totalizing force. This month, Fukunaga brings that force to his second TV show, “Maniac,” a Netflix series starring Emma Stone and Jonah Hill as participants in a drug trial that purports to do the work of decades of therapy with three pills.

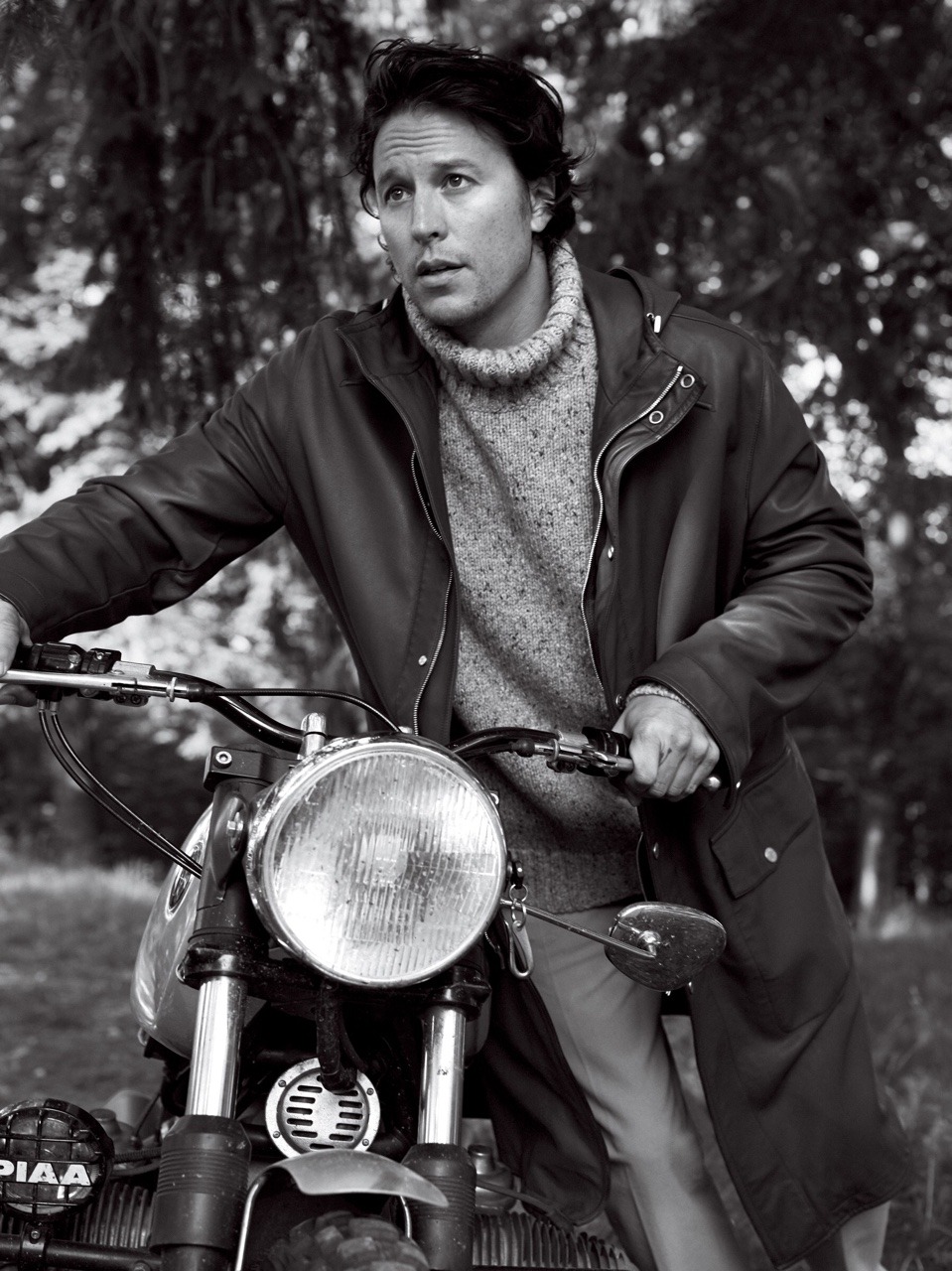

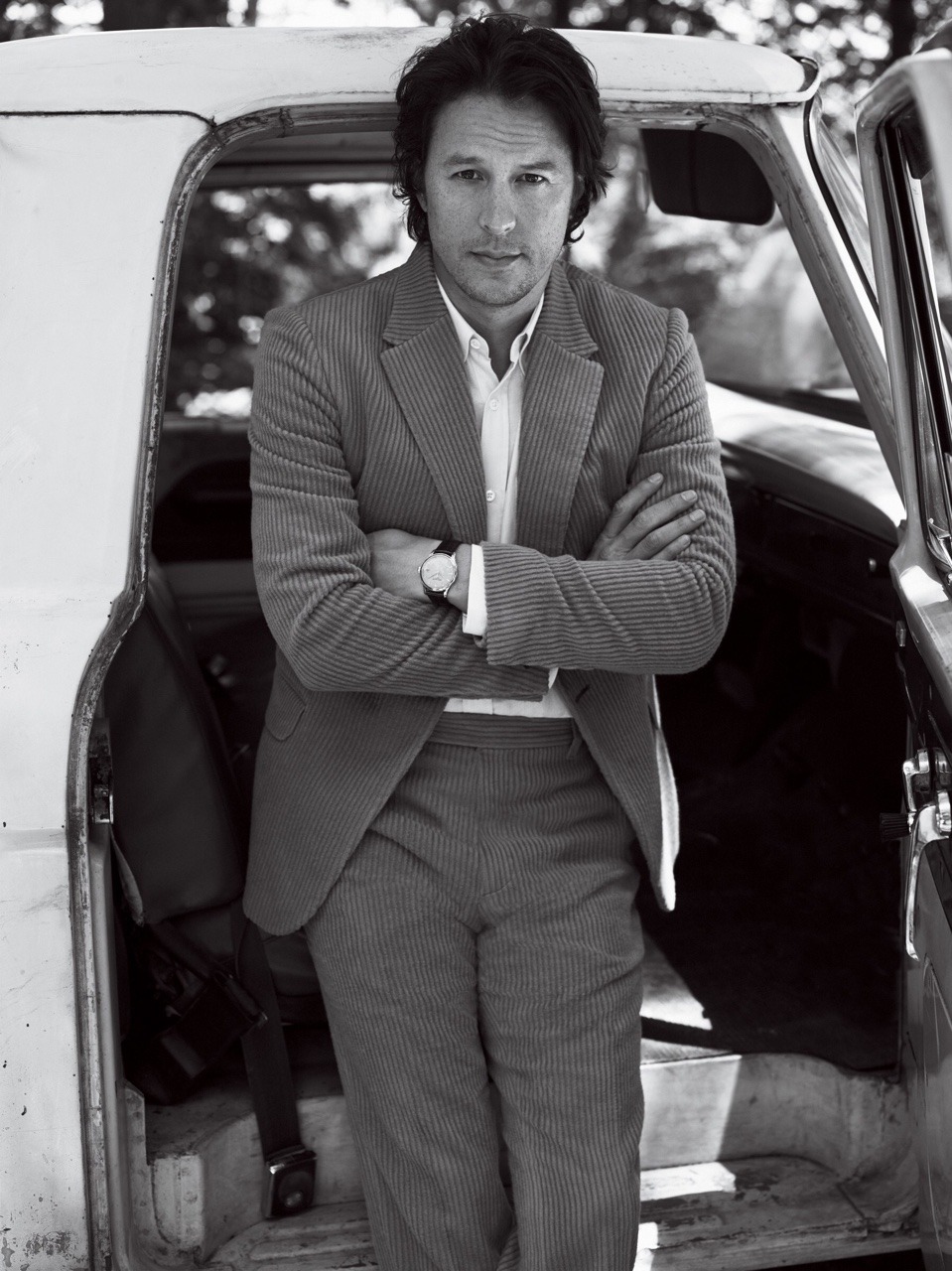

On a sunny day in late May, the director walked into the series’s bustling postproduction office in SoHo and was immediately beset on all sides. The show, set in a bizarre alternate world in which the drugs ingested result in vivid, psyche-plumbing experiences that bear a stark resemblance to existing film genres (’80s action-comedy, fantasy quest, etc.), was hurtling toward completion, and his attention was urgently needed everywhere — editing, special effects, color correction, scoring. Fukunaga is 41, tall and extremely handsome. He carries himself with an athlete’s bouncy elegance (until his early 20s, he wanted to be a professional snowboarder) and radiates an assured California calm. He can take a nap anywhere, at any time, a skill he learned while researching “Sin Nombre”: “We’d be on the railroad tracks for days at a time, and I learned how to sleep on gravel pretty well.” But this lackadaisical vibe belies his thrumming high standards and his obsessive eye.

Fukunaga has a devoted core of colleagues who have collaborated with him on multiple projects and talk, in quasi-religious terms, about the moments when they realized they had to just let go and let Cary be Cary, trusting his instincts and his process, however taxing that process could be. From each of his sets there are tales of his single-minded insistence on certain details: on finding the perfect church on a hill; the perfect petroleum refineries; the perfect exterior for Neberdine Pharmaceutical Biotech, the drug company where the majority of “Maniac” takes place. The location team showed Fukunaga hundreds of possibilities before finally uncovering the one that was just right. “It’s the hardest thing when you can feel dozens of people, literal breathing human beings who are standing next to you on a tech scout, for example, all being like, Can we just get back in the [expletive] bus?” Patrick Somerville, the creator and head writer of “Maniac,” says of Fukunaga’s determination. He cannot stand a mediocre job, Somerville explains. “That’s it. I think it’s vulgar to him.”

Fukunaga is aware that his exactitude has given him something of a reputation. He co-wrote the screenplay for the recent adaptation of Stephen King’s “It,” but did not end up directing it, as had been originally planned. “The studio just kind of pulled the plug when they felt like I was going to be too difficult,” he says, his voice a shrug. But it’s not that Fukunaga has a temper — he never even raises his voice. The vibe on the “Maniac” set was so amiable that during one visit, the crew was observing “Fukunaga Friday,” in which they all walked around with Fukunaga’s distinctive plaited pigtails, more and more of them as the day went on. By midday, one bald man was walking around with wire pigtails tucked beneath his hat.

In person, Fukunaga is affable and probing; he makes conversation, but not small talk, while cuddling his pit bull, which he adopted while on location for “Maniac.” He’ll recommend the Harper’s Magazine article about schizophrenia that helped him better understand Hill’s character, Owen, who is mentally ill; he’ll become a little abashed about the astrologer he sees (“Every time I’ve been to him he’s been really accurate”); and he’ll un-self-consciously entertain you with stories about his many experiences with ghosts — the poltergeist who slammed cabinets in his childhood home, the dead woman who touched his face in the middle of the night when he was 4, the ghost in a London apartment that made itself known with its vile body odor — told with both a childlike openness and a director’s cunning efficiency, relaying exactly the details needed to accurately imagine the ghost for yourself.

But for all his charm, Fukunaga is also implacable. “When someone comes into a meeting and says, ‘This is an orange,’ Cary will say, ‘Prove to me that this is an orange,’?” says Mara LePere-Schloop, an art director on “True Detective” and a Fukunaga regular. “It’s a very rigorous thing, and it will drive some people insane.”

As a teenager, Fukunaga became obsessed with the Civil War. When a janitor at his Sebastopol, Calif., high schoolhanded him a flier for a Civil War re-enactment, he went. He became a re-enactor himself, falling in with a crowd that was particularly devoted to realism; they would soak bits of their costumes in urine and excrement and try to be as historically accurate as possible. “There’s this thing in re-enacting called ‘having a moment,’?” Fukunaga says, “when there’s nothing around you that indicates that you’re living in 2018. You look left, and there’s 6,000 people that way, and you look right, and there’s 6,000 that way, and there’s no audience. The present tense sort of dissolves, and you really feel this sort of transcendental experience of being this other person. Sometimes you actually feel fear.”

“Having a moment” is the Rosetta Stone for Fukunaga, who uses his extreme, gnarly attention to material detail to vertiginously recreate the lived experience of people who are superficially nothing like him. Fukunaga spent his formative years growing up around Berkeley’s Telegraph Avenue, “surrounded by Berkeley protesters and communist bookstores and homeless people.” His Japanese-American father and Swedish-American mother divorced when he was 4, and he split time between them. His parents changed jobs with some frequency — his father worked for a generator company before eventually becoming an administrator at the University of California, Berkeley, and his mother was a dental hygienist before going back to school to become a teacher. Fukunaga spent time living in Mexico after his mother married a Mexican-American, which is how he learned to speak Spanish. He started making videos, like one about pirates, when he was 10. In his late 20s, after snowboarding for a few years and working on music videos, he went to film school at N.Y.U. His award-winning student film, “Victoria Para Chino” — a 13-minute Spanish-language short based on a 2003 news story about a tractor-trailer smuggling almost 100 immigrants across the border, found abandoned with 17 dead people inside — led directly to “Sin Nombre.”

There is something fundamentally athletic about Fukunaga’s directorial approach, the idea that with enough practice, research and experience, mastery becomes indistinguishable from instinct. His third feature film, “Beasts of No Nation,” about a child soldier — for which Fukunaga did years of research, including visiting Sierra Leone in 2002, at the end of the civil war there — was filmed in Ghana, where Fukunaga and other members of the crew came down with malaria. He shot the film himself anyway. Fukunaga explained to Idris Elba, one of the film’s central actors, the virtues of doing your own cinematography, ultimately inspiring Elba to learn how to operate a camera for his own directorial debut. “When he’s looking down the iris of the lens,” Elba says, “he can spot things, his intuition takes his eye and he can adapt right on the spot.” Working on “True Detective,” Matthew McConaughey made Fukunaga a T-shirt with the image of feet on a skateboard that said “Everything Lends,” a reference to his ability to find inspiration on the fly.

Fukunaga’s immersive tendencies extend to his hobbies, of which he has a shocking number. He skateboards, surfs, rides a motorcycle and used to practice capoeira. He lives in the West Village, but has a house in upstate New York, a two-hour drive outside the city, where he goes to relax and work in his wood shop, spending time alone or with friends. His polo horse is stabled nearby. He learned to ride after working on “Jane Eyre,” prohibited for insurance reasons from taking lessons with the cast. Because Fukunaga does not do things in half-measures, this somehow led to his becoming a devoted polo player. Trudie Styler, who appears in “Maniac” and is a friend of Fukunaga’s, says her husband, Sting, has described him as a “10,000-hour guy,” a reference to Malcolm Gladwell’s notion of the amount of time needed to master a craft. He’s the type of person who will put in the effort and “become not only proficient, but an aficionado,” she explains.

If this conjures some sort of swaggering John Huston with a snowboard, please let me clarify: Fukunaga is a distinctly Bay Area variation on the type, not macho so much as open-mindedly omni-competent. Yes, at some point, he and some buddies decided to learn as many skills as they could to survive the apocalypse — he’s not a prepper; it was more of a merit-badge thing — so he can sail a monohull, climb rocks, shoot a gun, use a bow and arrow and navigate with a compass. But he also has gorgeous handwriting, speaks several languages and loves many a lifestyle Instagram account. He just got a new cooking range upstate, the same kind as a French cook and lifestyle guru he follows, and he is thrilled about it: “It’s going to be sick. It’s wide, two ovens — you can do meat and your potatoes at the same time, your root vegetables.” He has seen a therapist. He may or may not currently be single (“sort of ... it’s complicated”), but has a reputation for falling madly in love. “The guy is a sensitive guy,” says Mick Casale, a friend and former screenwriting teacher of his at N.Y.U. “He comes over for lunch, and we just talk about love!”

“There’s an interesting juxtaposition between his personal self and his professional self,” says the director and actor Joshua Leonard, a close friend of Fukunaga’s. The two met when they both had short films at the Sundance Film Festival in 2005. “Cary is very different as a friend than he is as a director. As a friend, he is a big softy. As a director — I want to be very careful how I say this, and I want you to be careful if you use this quote — I don’t think he gives a [expletive] if people like him or not on set.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Fukunaga can be obsessively granular, because be believes the wrong detail can shatter a movie or TV show’s spell — its unique ability to enable us to have a moment. “Anytime something is slightly uncanny or just not quite right, it could potentially disturb suspension of disbelief.” The wrong detail is a disservice to the material, to the audience, to the project, and Fukunaga is painstaking about grinding them out. “It’s like sanding,” he says. “You just want to sand all the burrs away. So, you have to clean and clean and clean.”

“Is there something wrong with the arm?” Fukunaga asked on a warm day last September, matter-of-factly inquiring after the corporeal integrity of a spindly-armed purple koala. The koala, a puppet operated by a man with bushy white mutton-chops and a mustache, was perched in a fake eucalyptus tree, playing chess in Washington Square Park. Fukunaga spoke to the puppeteer with a studied normalcy, as if directing something made of artificial fur were an everyday occurrence. He’d been asking whether the movements could be less “plastic” when he noticed something wrong with a limb. “It looks like it’s hanging by a thread,” he said, squinting with concern. It was.

“Maniac” is so jam-packed with oddities that the koala, when it appears in Episode 2, is just one more surreal detail in a show bursting with them. The series is set in a New York that is similar to our own, but with a different history of technology. Office workers use computers with the black-and-green interfaces of ’80s IBMs. The city has a second Statue of Liberty — the Statue of Extra Liberty — in the East River. The central Brooklyn Public Library is a bus terminal. Washington Square Park is still full of chess hustlers, but some are animatronic puppets. Stranger still are the delusions, obsessively imagined miniworlds with the logic of waking dreams. Hill and Stone’s characters spend the entire series becoming other people in order to learn how they might be themselves.

Like them, Fukunaga immerses himself in other worlds to work through something more personal. “With ‘Maniac’ in particular,” he says, “both Patrick and I got excited about doing a year and a half of auto-analysis of ourselves. We’ve explored pretty thoroughly our relationships — sometimes directly, sometimes indirectly — with our parents and our siblings and our loved ones.” Both men put a lot of themselves into the script, but when I asked for a specific example, Fukunaga laughed — “I’m trying to think of one without exposing myself” — before demurring: “I love my parents, and I don’t want to throw them ... under the bridge? Under the truck?”

Fukunaga says he wonders after he has completed a project: Why did I make that movie? Why did I tell that story? His answers are often connected to his history. Fukunaga’s father was born in 1943 in a Japanese-American internment camp. He grew up knowing this. He interviewed his grandparents about their experience and studied the era in school. But when he looks back on “Sin Nombre” and “Beasts of No Nation” and the devastating circumstances they depict, “I think I was trying to explore the emotional side of myself,” he says. “I hadn’t allowed myself to understand what the internment experience must have been like for my grandparents, for their family, for their kids — my uncles and my dad.” He was using his work to get closer, by some emotional transitive property, to their trauma.

Fukunaga was recently looking at photographs of himself as a child, “and I was like, ‘Oh, [expletive], I looked like a little ethnic kid.’?” He was bullied at school. “There would be kids in school who would be like, ‘My dad says you’re a commie.’ I’m like: ‘That’s Chinese, you idiot. I’m Japanese.’ Things like that.” But today, people sometimes assume that Fukunaga is white. After “Beasts of No Nation” came out, Fukunaga remembers a Nigerian paper wondering “why this white man was coming in telling another grim tale about Africa.” He says that “because of my economic and racial upbringing, I’m not sure what group I belong to. And that gives me O-negative blood, where you can just donate to everyone. I feel like a third-culture kid. I feel part of nothing but part of everything.”

As the entertainment industry has become more conscious of making room for different voices — however slowly, however haltingly — that often involves limiting those voices to their identities: Black directors should make shows about blackness, women should make shows about being women. But as an Asian-American man, Fukunaga did not grapple with his family’s history by making a movie about the internment camps: Rather, his family’s past made him interested in trauma more generally.

“It seems like Cary could apply his intelligence to any project, that he can intellectualize telling the story of anything, even if it doesn’t have to do with him,” Jonah Hill says. “I’ve worked with other filmmakers where even if the material’s not them, then it feels like them. I don’t think he feels like Jane Eyre. I think he knows the material so well, and he’s so proficient, that he can do it really well.” Fukunaga forges connections across identities — to immigrants, to a 19th-century female English orphan, to a child soldier, to a delusional schizophrenic — not by subsuming the characters to himself but by treating them as different yet decipherable. It’s an old-fashioned faith in expansiveness that is both risky and increasingly rare.

Fukunaga is working on a number of projects, including an adaptation of “The Black Count,” the true story of Alexandre Dumas’s Haitian father, and one about the days leading up to Hiroshima. Just eight years ago, he directed “Jane Eyre,” about a beloved female character created by a famous female author, but now he feels hesitant to take on certain female-driven scripts because he worries that his gender would consume the conversation around the project. “What if we’re getting to the point where we’ll say you’re not allowed to tell a story about someone who is nothing like you?” he asks, rhetorically. “If people can tell stories that aren’t their own, it helps make the world smaller,” he says, “but it requires a sensitivity and an attention to detail.”

When he was in film school, Fukunaga did write a story about an internment camp. “I was interested in it, but didn’t know how to make that story yet. If anything,” he says with a hint of steely self-awareness in his voice, “whenever anyone has said, ‘You should tell this story,’ I’ve pivoted and done the opposite.”